Now we’re into a pre-election period, it seems like a good time to return to the topic of Labour’s Twenty-Point Lead – and what’s about to happen to it.

This post is in two parts. Part 1 fills in some historical background, looking at what happened in the run-up to the previous seven General Elections (1997, 2001, 2005, 2010, 2015, 2017 and 2019). Part 2 draws some tentative conclusions from all this history and sketches out some predictions for the current General Election. You may well want to skip to the bit with the predictions; just scroll down to ‘Part Two’ or click here.

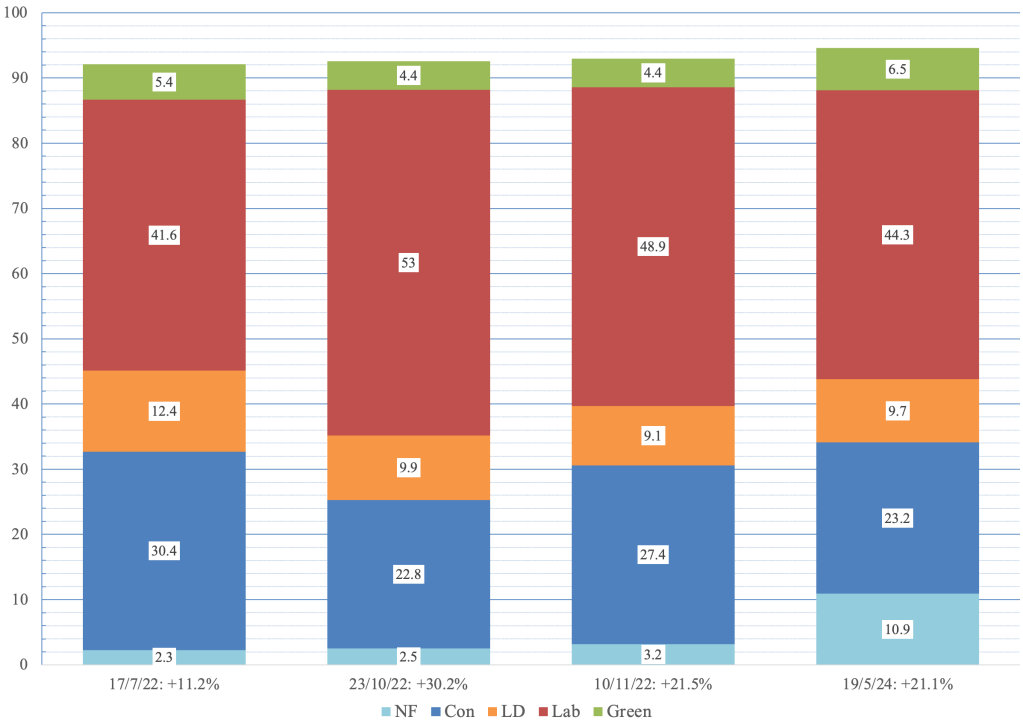

Have they gone? Right, let’s do some (recent) history. First, a quick precis of the previous post. A big lead is a big lead, but some Labour leads are more fragile than others – and a lead which is dependent on the Tory vote being preyed on from the Right is more fragile than most. And that’s what’s been happening lately. In the eighteen months from November 2022 to May 2024 Labour’s average polling lead over the Tories only fell from 22% to 21%, but this comfortable lead masked a drop in Labour’s actual polling of 5%, from 49% to 44%. The average voting intention for the Reform Party, meanwhile, rose from 3% to 11%, putting the Farageists in a comfortable third (party) place. In short, it’s Reform UK, not Labour, who have been making gains at the expense of the Tories.

A recomposition of the Right vote under the Tory banner, between now and July, can’t be ruled out – it has, after all, happened twice before, in the run-up to the two most recent General Elections. It would leave us looking at polling figures in the region of Labour 44%, Conservative 35%: a solid lead in most times, but not a strong position to be in at the start of an election campaign, given the tendency of the Tories and their friends in the media to throw everything they’ve got at Labour, and the tendency of Labour’s support to fall.

Part One: The Tendency of Labour’s Support to Fall

To start with, here’s where we are now.

What you see here is Labour’s peak two-week average polling, since Keir Starmer became leader, under the respective Tory leaderships of Boris Johnson (Labour 41.6%, +11.2%), Liz Truss (Labour 53%, +30.2%) and Rishi Sunak (Labour 48.9%, +21.5%). (‘NF’ of course refers to Nigel Farage, majority stakeholder in the Reform Party.) As we’ll see later, during a General Election campaign it’s very unusual for Labour’s polling to go above the peak level they’ve polled in that Parliamentary term – and Liz Truss is no longer Tory leader. So a figure like 48.9%, this time out, is probably as good as it’s going to get – and the result on the day could be a lot lower.

To estimate how much lower, I’m going to chart three sets of data points, across multiple Parliamentary terms: the parties’ average support at the point in a Parliament when Labour support was highest; the parties’ average support at the point the next election was called; and the parties’ actual support in that election. (It’ll be clearer once we get going.)

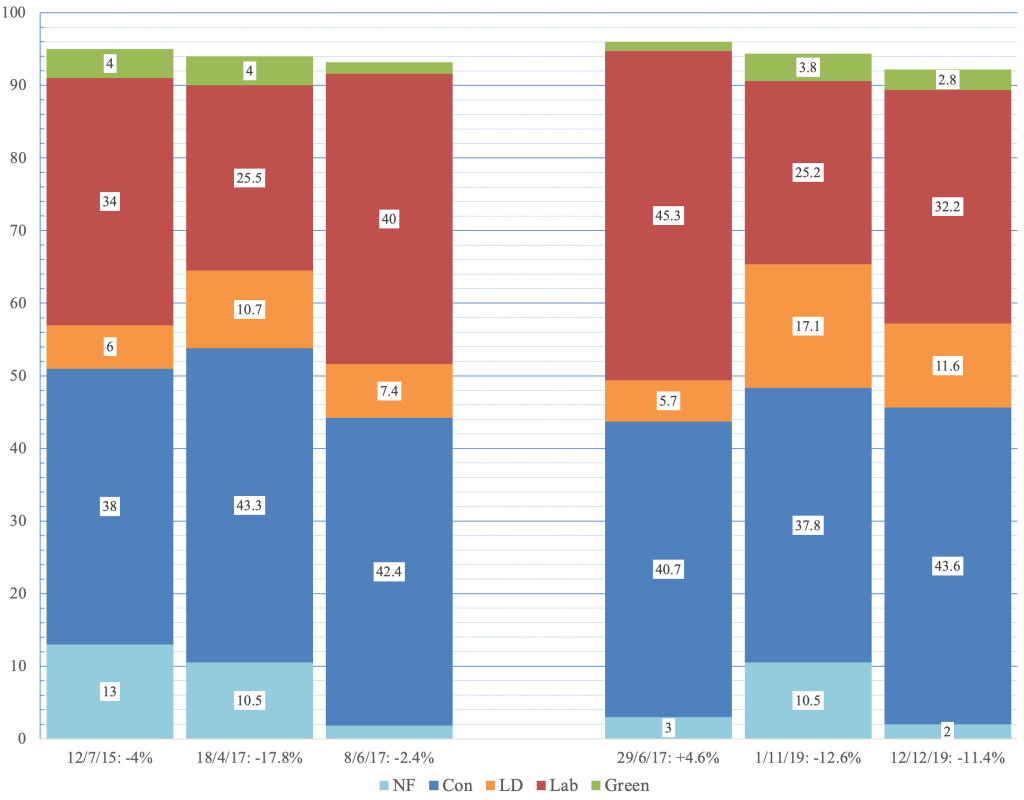

To begin with, here’s a chart covering every General Election that Labour has ever won from opposition and with a workable majority. Hope it’s not too crowded!

OK, so just the one. NB ‘NF’ here doesn’t refer to Nigel Farage – or rather, it does (UKIP contested 194 seats in 1997 and got 0.3% of the vote, with Farage the only candidate to retain his deposit) but it also refers to the Referendum Party (who got 2.6% and lost 505 of 547 deposits). There is also a Green vote on this chart, but it’s hard to see; they took 0.2% of the vote.

Housekeeping done, what do we see? We see that, in the high tide of New Labour, the Tories were at one point reduced to a two-week polling average of 18.5% – only a few points clear of the Lib Dems – with Labour enjoying an average 43.5% lead(!). In the second column we see that the Tories had recovered a fair bit by the time the election was called – at the expense of both Labour and the Lib Dems – although Labour still went into the campaign polling, on average, 55% of the vote (! again).

Lastly, we see the effect of the short campaign. Assume for a moment that the Eurosceptic Right exclusively cannibalised the Tory vote, so we can think in terms of the ‘Right’ vote rising from 27% to 33%. We can now see a two-way drift away from Labour, and a substantial one: almost 12% of people, having intended to back Labour six weeks previously, actually voted Tory, Lib Dem or possibly even Green, or abstained. The Tory Party still faced a wipeout – a lot of those Lib Dem votes fell badly for them, and leakage to the Referendum Party can’t have helped; the Tories finished in 1997 with only 165 seats (which is 37 fewer than Labour took in 2019). But 30.7% isn’t an unrecoverable position for an opposition party (as subsequent elections went on to show). Put it this way, when you look at that chart 30.7% is a hell of a lot better than 27.2%, let alone 18.5%.

And then there’s that fall in Labour support. Even if half of the support Labour lost went to the Lib Dems, and even if the effect of the other half was undercut by leakage to the far Right, it’s still the case that 1997’s short campaign saw Labour’s support decline by more than a fifth, from 55% to 43%. This, not to put too fine a point on it, is not how I remember that election. I remember the rallies and the supportive TV coverage, and the fact that people actually liked Tony Blair back then, and of course I remember the result; in retrospect the campaign seems almost like a coronation. But there was a lot of press hostility – a lot of attempts to spread fear, uncertainty and doubt about New Labour and Blair in particular – and a fair bit of it evidently went home. And, although 55.1% is a very comfortable base to go into an election on, it’s not 62%. There was a moment when New Labour was at its electorally shiniest, if you’ll pardon the grammar, and it was back in 1995; it wasn’t on the day when the 1997 election was called, and it certainly wasn’t on the day when the votes were cast.

How about the other elections Labour won under Blair? Here you go:

(Not sure what’s going on with columns 2 and 3 on the left; Labour appear to have lost around 3% to ‘Others’, which is not what the figures say. I imagine it’s an artifact of polls which excluded non-UK-wide parties.)

Housekeeping aside, it’s a similar story – but one that brings diminishing returns for Labour. Firstly – after both the 1997 and 2001 elections – we see what was presumably post-election euphoria producing frankly improbable support numbers for Labour. Then Labour’s support drops over the course of the parliamentary term, by 14-15% in both cases; 8-9% goes to the Tories, 3-4% to the Lib Dems. During the 2001 and 2005 short campaigns, Labour loses more support, although (unlike 1997) they lose it to the Lib Dems, not the Tories. Labour then comes through and wins the election both times – but on a lower share of the vote in 2001 than 1997, and a lower share in 2005 than 2001.

Note the diminishing returns. There’s a consistent pattern of Labour losing support during election campaigns and regaining it afterwards. Having won the elections in 1997 and 2001, at the start of each of those terms Labour is considerably further ahead than they were at the election itself – but not as far ahead as they were at the previous peak. The “early enthusiasm, later disillusion, then lose a bit more in the short campaign” model was one that left Labour at a lower starting point, both in absolute terms and relative to the Tories, every time. And there’s only so low you can go before you run into trouble.

Trouble duly arrived in Labour’s third term. For some reason, post-election euphoria wasn’t such a big thing after the 2005 election; Labour support peaked in the low 40s. From then until 2010, Labour lost support as before – but now, for a novelty, to both opposition parties. During the short campaign the Lib Dems made gains at Labour’s expense, while the Tory vote was eroded from the Right. (Perhaps. Arguably there’s an ‘NF’ slice missing from the second column on the left; it was only after the 2010 election that pollsters started recording UKIP (and Green) preferences instead of lumping them in with ‘Others’.)

Inevitably, Labour lost the next election. Support recovered rapidly after the formation of the Coalition government, though: what presumably wasn’t post-election euphoria took Labour support, under Ed Miliband’s leadership, up into the low 40%s. (It looks as if most of the 2010 Lib Dem vote had gone to Labour. Wonder what that was about.) Between that 2012 high and the 2015 election, however, we see a familiar-looking two-stage squeeze. This time the losses in support are all to the Tories; the Lib Dems have actually lost support since 2012 (wonder what that was about). The Tory vote is up 2% from 2012 when the election is called and another 3% on the day, while the total Right vote is up by 9% and 2% respectively. The Tories, in other words, bucked tradition by not only putting on support of their own, but eating into the UKIP vote during the campaign rather than having UKIP erode theirs. (Wonder how they did that.)

The story so far: the data show that Labour can win a majority from opposition by building up a frankly unrealistically huge polling lead, then going into the campaign with a polling lead that’s merely monstrous and letting the Tory press whittle it down to ‘Large’. The data also show that the only day on which Labour can win a majority from opposition is 1st May, and the only year is 1997, but that’s data for you. Longer-term data show that Labour’s polling tends to be high after an election – even one they’ve lost – and then tends to get squeezed, initially by the Lib Dems and more recently by the Tories; this happens in two stages, over the course of a Parliament and during the short campaign. This happened over and over again, from 1992-7 to 2010-15, with Labour’s high and low polling figures charting lower every time. Something had to happen to break the cycle.

Here are 2017 and 2019.

Labour’s peak polling, between the 2015 election and the day Theresa May called the 2017 election, was 34% (trailing the Tories by 4%). By the time the election was called, this weak position had been further eroded by a familiar two-way squeeze: Labour were losing support to the Tories and to the Lib Dems (yes, they’re back). The Tories, moreover, were holding their ground against UKIP and even clawing some support back. It all added up to a near-18% lead, for the Tories. With Labour on the ropes and the press in her corner, Theresa May must have thought she was going to cruise to all-out victory.

It wasn’t to be, of course. On the day, the Tories absorbed large chunks of the Kipper Right – not for the last time – but the Right as a whole lost ground in a big way, dropping from 54% to 44%; Labour picked up votes from the Right and indeed from the Left and the Centre. The Tories’ final result of 42.4% was – as you’ll see if you scroll up a bit – a huge improvement on anything the party had got under the four Conservative Party leaders before Theresa May; in fact it was the Tories’ biggest share of the vote at a General Election since 1983. It was just a shame that when the Tories polarised the country around patriotism and authoritarian leadership, the Labour Party was in a position to polarise it right back. As I wrote a bit back,

when he became Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was strongly associated with a couple of ideologies which he’d upheld for thirty years as a backbencher: an ideology of human equality, of every person (anywhere in the world) mattering as much as any other; and an ideology of constructive empowerment, of mobilising people to make the world a better place. As Labour leader he found, probably to his surprise (certainly to mine), that appeals voiced in terms of these ideologies were actually quite popular … his outsider status [also] let him appeal – consciously or not – to another ideology that’s flourished in Britain in the last decade: this combines short-term pessimism with an openness to big, dramatic changes … [we could] call them “Equality Everywhere” and “Let’s Get To Work” … [and] “Big Bang? Bring It On!”

It was a powerful combination and got a lot of people enthused, many of whom probably hadn’t thought of themselves as particularly left-wing. Admittedly, it would have been nice if Labour had worked the trick of building a support base without also motivating its opponents. Corbyn and May had a very similar problem: like 42.4%, 40% of the vote would have been quite enough to win, if only the other lot had got significantly less. But I’m not going to accentuate the negative – there are plenty of people to do that. We came from behind and turned what looked like being a landslide into a hung parliament, having demonstrated along the way that radical and even anti-imperialist policies had genuine resonance with the people of Britain; 2017 was a good result, a starting-point that could have been built on, given a bit of goodwill and a bit of discipline. (Although perhaps the discipline was needed much earlier… but enough! or too much.)

The 2017-19 parliamentary term began, as had some earlier terms, with strong polling for the Labour Party that a lot of people now wished they’d elected; 2017’s 45% compares favourably with 2005’s 41% and 2010’s 43%. Fast forward to November 2019, though, and – although we’re in very unusual conditions (the Commons in deadlock, a new Tory leader, new centrist parties breeding like lice) – the squeeze on Labour’s support is all too familiar. The Farage party is back out of its box, and the Right overall up 5%; the Lib Dems are up 12% and the Greens 3%, and Change UK also existed. All of this, like the surge in Tory and Lib Dem support in 2015-17, came at the expense of Labour, whose support is down, again, to 25%. In fact there are hardly any differences between how the parties were polling at the point when the 2017 and 2019 elections were called, except that in 2019 the Conservatives began 6% lower than 2017 and the Lib Dems 6% higher. Oh, Jo Swinson…! Great days.

What happened next was… pretty much all the same things that had happened two years previously, only on a smaller scale. While Labour may again have attracted the more anti-establishment element of BXP support – along with significant numbers of Green and Lib Dem supporters – the Tories held on to their support and pocketed most of the BXP vote thanks to a stand-down agreement. Labour’s support went up 7%, but the Tory vote went up 6% – and started out 12% ahead – so they still got a big majority. The end.

Part Two: The Past is Prologue

What tendencies can we derive from the history of past election campaigns, and what predictions can we extrapolate from them? What kind of election campaign is this one going to be?

I suggest that:

1. Labour support will fall.

In all the last eight General Elections (including 2024), Labour has begun the election campaign below peak polling; in five of the last seven, Labour’s support has fallen further during the short campaign. The exceptions are the two Corbyn campaigns, which were marked by highly unconventional campaigning (large-scale personal contact, radical commitments, sincerity etc). In the 1997 and 2001 election campaigns, Labour’s support fell by 28% and 17% respectively; falls were smaller in the next three, but partly because the starting position was much lower. On past form it would not be at all surprising if, on polling day, Labour’s current polling was down by 15% – which is to say, down 6 percentage points, in the region of 38%.

2. Lib Dem support will rise.

Yes, really. In 2001, 2005 and 2010, Lib Dem support was higher when the election was called than at Labour’s polling peak, and higher again at the election itself. The first of these held good in 2017 and 2019, although Labour campaigning drove it back down again by the time of the election. Lib Dem polling is currently above the ‘Labour peak poll’ level, and it’s a fairly good bet that the Lib Dem vote on the day will be higher again. The Lib Dems have dramatically improved visibility during an election campaign; anyone wondering vaguely who they might vote for suddenly has a much larger choice, and some will take it. Unless they’re squeezed out by a more visible radical contender – which really doesn’t seem likely – the Lib Dems are likely to have a good campaign and finish on 12% or so compared to their current 9%.

It’s also possible that Green support will rise further, but that’s purely on the basis of how it’s risen already since Labour’s polling peak (and also on the basis of <gestures>All This). Historically the Greens don’t tend to put on support during the short campaign, probably due to the ‘irrelevance effect’ (more on which below). If they have a good campaign and a couple of feasible target seats, that could change this time.

3. Right support will rise.

Support for the Right as a whole – the Tories plus the Kippers in whatever guise – has risen between Labour’s polling peak and the calling of the next election in all eight Parliamentary terms covered here, including the current one. Support for the Right has risen further during the short campaign in 1997, 2010 and 2015, and held steady in 2001 and 2005. The latter is a possibility this time round – the Tories were on the mat back then, too. But, as with the Lib Dems, I think it’s likely that the trend of 2010 and 2015 was only interrupted by the unusual approach of the Corbyn campaign, and that we’ll see it resumed this time. The combined Right vote has already risen from 30% to 34%; it could finish up in the high 30s or above.

4. The Tories will absorb (most of) the Reform UK vote.

Reform UK polling has flagged a bit since April, but they’re still registering around 11%, a full % ahead clear of the Lib Dems. What happens to that bloc of support on July 4th is one of the big questions of this campaign.

There are three main possibilities, as far as I can see. Firstly, it’s possible that there could be a stand-down agreement to the benefit of the Tories, as there was in 2019. This, needless to say, would be very bad news for Labour, not only because it would bump up Tory support but because Reform UK’s remaining support would effectively be targeted to damage Labour. Secondly, it’s possible that voters will feel that Reform UK are a good ‘sod the lot of them’ option but not someone you’d actually want to vote for, and return – perhaps reluctantly – to the two main parties, as they did in 2017. The third option is that Brexit Party support holds up, as UKIP support did in 2015 (541 saved deposits out of 614).

A stand-down agreement doesn’t seem very likely. While Reform, like the Brexit Party and UKIP, defines itself in opposition to all the main parties, it doesn’t have a headline single issue and consequently doesn’t have any obvious grounds for declaring an alliance with a faction within one of the main parties (which is basically what happened with BXP and Johnson in 2019). Moreover, not having a headline issue has enabled Reform to serve as an all-purpose alternative for disaffected Tory supporters, which in turn has made “not Conservative” a much stronger part of the Reform identity than it was for the Brexit Party or UKIP. On a personal level it’s also hard to see Farageists wanting to line up behind an out-of-touch multi-millionaire banker turned failed politician who, I’ll start that one again. It’s hard to see Farageists wanting to line up behind a multi-millionaire etc etc with a name like Sunak. (Not All Farageists, certainly, but I’m pretty sure that race is a factor for some.)

How about the 2017 option? Reform UK are currently saying they will stand a candidate in almost every seat, Labour or Tory, and perhaps that’s what they’ll do. But maybe they’ll just seem a bit irrelevant, as UKIP did in 2017, when voters make their choice at the end of a hotly-contested and highly polarised election campaign – or even at the end of the low-stakes, tepid and dull campaign we’re now entering. If the ‘irrelevance’ effect does kick in – if, come July, the two main parties have managed to persuade the British public that it actually matters who they vote for – I can’t see the drift away from Reform benefiting Labour; certainly Starmer’s party isn’t going to pull in a “these politicians are rubbish, let’s shake things up” vote, as Corbyn’s arguably did. (If Labour under Starmer does try to appeal to Reform voters, I fear they’ll be appealing on the basis of flying the flag and stopping the boats.)

The third possibility takes us back to 2015: what if Reform UK stand and do well? In that case most of these here prognostications of doom will be irrelevant: however high the notional ‘total Right’ vote goes and however much the Lib Dems and Greens erode the Labour vote, the Tories will still be looking at a very bad second place (although our awful electoral system will soften the blow; more on that below). The sting in the tail is what happens next. Clue: were UKIP more influential over UK politics after the 2015 election, or less influential? Think carefully. If the polls – as far as Reform and the Tories are concerned – stay where they are now, after July 4th we’ll be looking at a permanent invitation to Any Questions? and to the news programmes for Reform UK, who will have got more votes than the Lib Dems but got no seats at all, and will be gearing up for the next election under a slogan like “Stop the Steal – Kick Out the Liberal Elites!”. Which will in turn make a really terrific combination with a weak Labour PM obsessed with trimming to the Right. Hey ho.

If I had to call it I’d say that we’re most likely to be looking at scenario #2, the irrelevance effect, but almost exclusively to the benefit of the Tories. So from the current polling levels of (say) 44% Lab / 24% Con / 12% RefUK we’d be looking at something more like 46%/32%/2%. Factor in the previous predictions – that Labour will probably lose support during the short campaign to both the Lib Dems and the Tories – and we have figures in the range of Labour 36-40%, Conservative 36-8%, Lib Dem 11-13%.

If the Reform UK vote does hold up, on the other hand, those same assumptions give figures in the range Lab 38-42%, Con 28-30%, RefUK 12-14%, LD 11-13% – which look a lot more comfortable for Labour, although I’m afraid they don’t add up to as much of a landslide than you might think. One final point, which is less a prediction than a statement of fact:

5. The electoral map will favour the Tories

In the course of writing this post I’ve plugged some figures into a ‘swingometer’ app, based on the 2024 boundaries (which would have given the Tories a majority of 94 in 2019 instead of 80). It’s surprisingly(?) hard to get it to come out with a Labour majority. However low the Tory vote goes – even if the Right vote is split with Reform UK – it seems that Labour needs to get over 40% of the vote to assure a majority. (40% Labour, 28% Tory? Hung parliament.)

Put that background knowledge together with all the above, and I’m not optimistic. (I’m not optimistic about a Starmer government even if they get a landslide, but that’s a different issue.) In two months’ time I think we’ll be looking at one of two scenarios: a small (<20) Labour majority, with a Tory Party reduced to Labour-2019 levels and Reform UK champing at the bit; or a hung parliament, quite possibly with the Tories as the largest single party. (36% Conservative, 40% Labour? Hung Parliament, Tories largest single party.)

UPDATE These figures are calculated using the “swingometer” app at electionpolling.co.uk. Other Swingometers Are Available, and in point of fact the Electoral Calculus swingometer is considerably more optimistic. On inspection this appears to be because the EP swingometer is applying uniform national swings (UNS) rather than using what EC gnomically describes as “sophisticated predictive models”. This makes a big difference to how vote %s translate into seats – the difference between, say, 310 Labour MPs (and a minority goverment) and 350 (and a majority of 50). On the other hand, a sophisticated predictive model is only as good as the assumptions it’s built on, and General Elections are such sui generis events that at least some of the assumptions held by pollsters going in are liable to be proved wrong.

So you pays your money and you takes your choice. I suppose, for completeness, I should revisit the conclusion in the previous paragraph and say:

In two months’ time I think we’ll be looking at one of two broad scenarios. One is a safe but not substantial Labour majority, somewhere between the mid-teens and 60, with a Tory Party reduced to Labour-2019 levels and Reform UK champing at the bit. The other is a partial Tory revival leading to a precarious Labour majority, or possibly even a hung parliament: depending on how the votes are distributed, even a substantial Labour lead in total votes could result in the Tories being largest single party in the House of Commons.

There, much better.

I still hope Labour win, of course; if nothing else, they offer a change in direction from the Tories. (Also, if they lose they’ll only blame it on the Left, and I don’t want to go through all that again.)

One Comment

That’s very cheery Phil. Let’s hope you are being far too pessimistic! Does your swingometer take any account of MRP or tactical voting? Feels to me like the mood is overwhelmingly GTTO.